Food Production in the Gaza Strip, by the numbers

With the recent conflict between Hamas and Israel, I can’t help but think of the long-term implications of what happens when the dust settles. This is a food blog, so I’m obviously biased towards thinking of food and its production, and I decided to do my best to give a bird’s eye view of what’s going on.

For context, the Gaza Strip has been under a near two-decade long blockade set forth by Israel. This blockade prevents certain things from getting in and out, and, as a result, since 2005, local food production in Palestine has plummeted by 30%. About 63% of Gaza's population relies on international groups for food and basic services, according to the UNRWA.

Thanks for reading The Sketchy Guy! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

But the challenges facing Palestine are more complex than just those few sentences, so let’s take a deeper look.

I should note, this is just a recap of the situation, and I am no expert. Read a book if you want that.

What’s farming like in the Gaza Strip

Despite a very dry and arid land, Palestine and Israel both have significant agricultural potential and ability.

Israel has over 1m acres of farmland. About 75 percent of all Israel’s domestically grown vegetables come from the Gaza border area, as does 20% of the fruit and 6% of the milk.

The heavier clay-based soils of that border hold enough moisture and fertility to support rain-fed agriculture, and local varieties of olive, date palm, citrus and grapes have been uniquely adapted over millennia to cope with the saline conditions. Not to mention Israel’s advancements in water agricultural farming, including desalination and wastewater reuse.

Source: https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Israel_Agriculture_Crop_Areas_2017.png

Meanwhile, according to Middle East Monitor, Gaza produced about 70k tons of fruits in 2014, and in 2022, agricultural production accounted for about $430 million, or 6% of its GDP. There is evidence that they can, indeed, be self-sufficient in agricultural production. While small-scale family farming is the prevailing type of agriculture in Palestine, something that differs starkly from Israel, the local crop variety - dates, olives, etc - share a lot of similarities.

Not bad, right?

Satellites reveal the difference between small-scale family farming in southern Gaza (left), and highly subsidized industrial agriculture in Israel. Google Earth, CC BY-SA

However, despite nearly identical soil and climatic conditions yields in Palestine are about half of those seen in Jordan and only 43% of those produced in Israel. And there are a few reasons for that.

War destroys water infrastructure

There are many reasons to hate the Israeli blockade, but one of the more nefarious symptoms is the ongoing water crisis in Gaza.

While Israel provides around 10% of Gaza’s water, the other sources of water come predominantly from groundwater wells, which is rife with nitrate pollution.

The chain of events is simple; water quality in Gaza is poor due to a list of reasons (over-pumping and wastewater contamination, to name a couple), so it requires treatment. During war, treatment centers get damaged, raw sewage gets mixed in, and people ingest whatever diseases exist within.

A good example of this can be found during the Israeli airstrikes in 2008, 2014, and 2018.

In the 2014 war, Israel hit Gaza's only power generation plant, and many of its water sewage treatment centers were forced to close. As a result, Gaza had a buildup of raw sewage in its Gaza Coastal Aquifer, and was forced to release huge tons of waste water into the sea. You can see the dramatic increase in reported diarrhea cases during that year compared to the year after.

‘The impact of attacks on urban services II' (Pg 24) Michael Talhami and Mark Zeitoun

Luckily, since then, there have been successful international efforts to clean this sewage up. But, following the most recent October attacks, Israel again suspended water and electricity for about a week, raising concerns about the sanitary conditions that Gazans were forced to exist under.

On the other hand, the state of Israel has one of the best water qualities in the world, and has been criticized for not doing enough to alleviate the water issues to their neighbor; as the two states share resources, Israel essentially has the power to turn on/off access to water for the Gaza strip.

To be fair, certain Israeli citizens have done their part to improve Gaza’s water situation, such as this billionaire donating two water generators in 2021. But lifting the blockade would obviously have a larger impact.

Palestine is not free from my criticism either. Despite the high number of food insecure Palestinians, the agricultural sector only made up one percent of the Palestinian Authority’s (PA) annual budget in 2015. Contrastingly, a whopping 26 percent was allocated to the security sector (some might say necessarily so).

War discourages farming

The issue is not just the farming of food; it’s also the land where food can be grown.

Israel's 'buffer zone' policy, an imposed no-go zone, restricts access to much of Gaza's agricultural lands. While official figures are murky, estimates say this zone extends between 300 and 1,000 meters from the Gaza-Israel Green Line border, encompassing 30% of Gaza’s agricultural land. Those who stray too close to these areas risk being shot and their equipment confiscated or destroyed.

A view of the the Gaza Strip’s ‘no-go zones’. Source: UN

And once again, I have to come to Israel’s defense, as Hamas has not made things easy for farmers along the green line either. Israel employs a lot of Thai workers, and many have been scared off by Hamas terror tactics, leading to decreases in Israel’s agricultural output.

Same shit, different side.

War affects imports and exports

Gaza and the West Bank, often grouped together in economic analyses, suffer massive annual deficits of $6.6 billion. In general, Palestine imports much more than it produces and sells.

Occupation isolates the Gazan people from international markets, and thus compels them into overwhelming trade and economic dependence on Israel, which accounted for 80% of Palestinian exports and supplies 58% of its imports in 2019.

Looking at this world bank photo, you can see just how the increase in imports can be traced to the initial enacting of the blockade.

Source: World Bank

The challenges don't stop with internal production either. External conflicts, like the Russia-Ukraine conflict, have further strained the food economy. As an example, prices of flour mills surged by roughly 20% three months after the initial Russian invasion, as Russian and Ukraine are responsible for nearly 30% of the world’s grain resources.

War erases food culture

Not tragedy is comparable to the loss of human life, but there is a somewhat hidden dilemma also going on after these wars, one that takes longer to notice; the deterioration of history and traditions, especially pertaining to food.

Some are more obvious than others. There are many reported cases of olive and fig trees serving as collateral damage of settlement disputes. An estimated 100k olive trees were destroyed between 2000 and 2012. And even the Israeli military has confirmed that it sprayed aerial herbicides at least thirty times in and along the border with Gaza between Nov. 2014 to Dec. 2018.

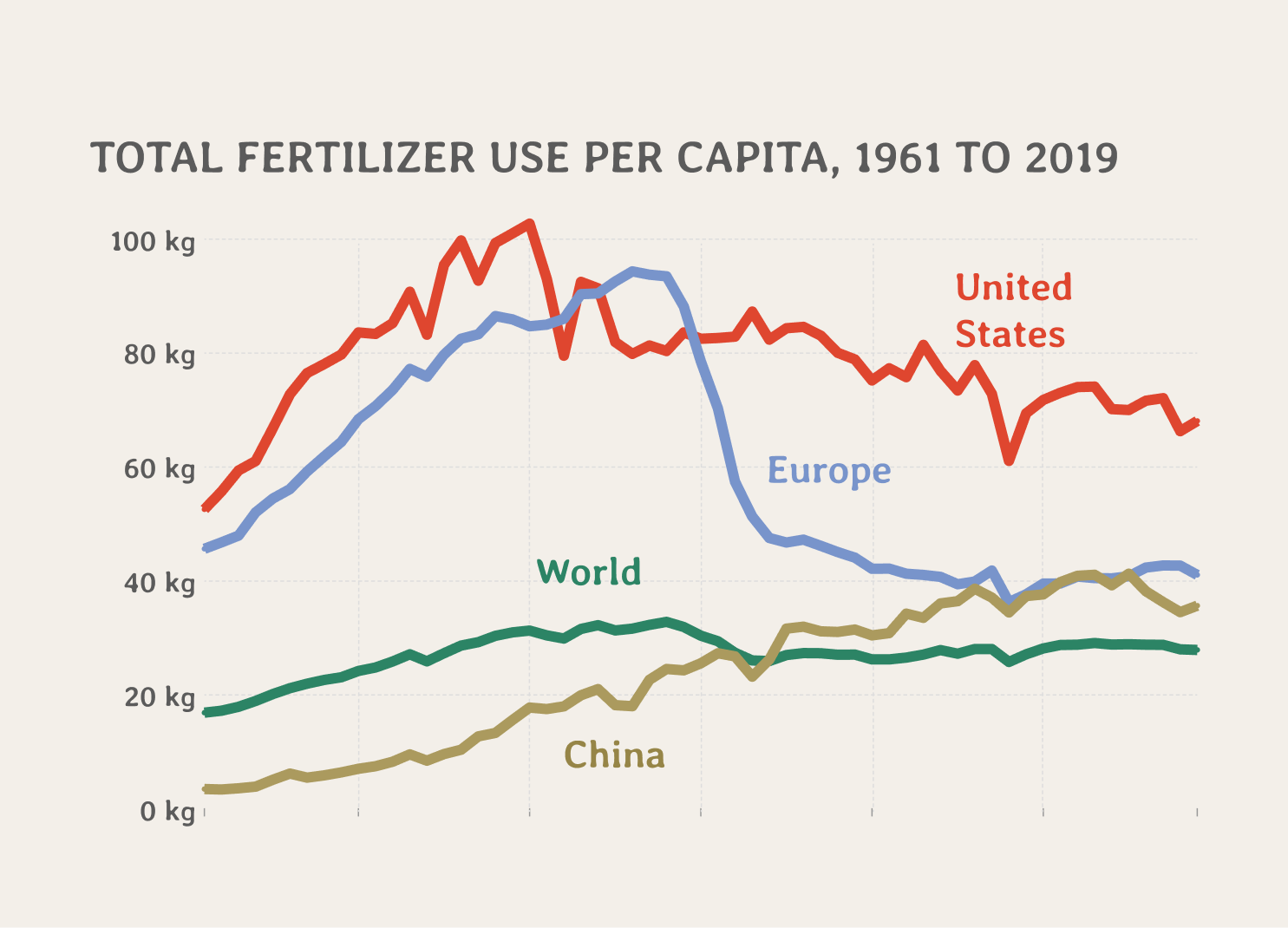

But there are other, more hidden symptoms. As an example, many farmers have become dependent on imported synthetic fertilizers and pesticides, increasing the cost of local production and undermining the soil biology of their farmland.

Increased dependence on hybrid seeds has already displaced many nutrient-rich, traditional baladi (local) seeds.

The traditional Gaza version of knafa, a popular Middle Eastern pastry, is becoming rarer to find outside of Gaza because border blockages and tightening finances.

These examples are few, but they are at the heart of Gaza’s food culture. And yet, the priorities of war overtakes the need for their preservation, resulting in their slow decline.

In conclusion

A simple blog post is not enough to explain the complexities of the food system in Israel and Palestine; a book would be more appropriate.

But during the fog of war, it is important - maybe crucial - to look a little further into the future, and do our best to understand that casualties of war are not just drawn rom bullets.

There’s a lot more to be said, but I’ll end with this; I unequivocally support a ceasefire between Israel and Hamas.

Thanks for reading The Sketchy Guy! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.