Comparing the Water Content of Raw vs. Cooked Meat

Cooked food appear denser in nutrients compared to its raw food because there's less water calculated in the weight

For this blog, I looked at the weight of certain foods, and how a food's makeup is more than just the macronutrients we all know (proteins, fats, and carbohydrates). One of the most basic and overlooked part of what we eat is the amount that is a water…it’s everywhere, even in foods you’d least expect.

The tldr of this blog:

- most meat is like 60% water

- raw meat is usually heavier than cooked meat because it loses water; about 25%

- cooked version appears denser in nutrients like protein and fat compared to its raw counterpart because there's less water diluting these component

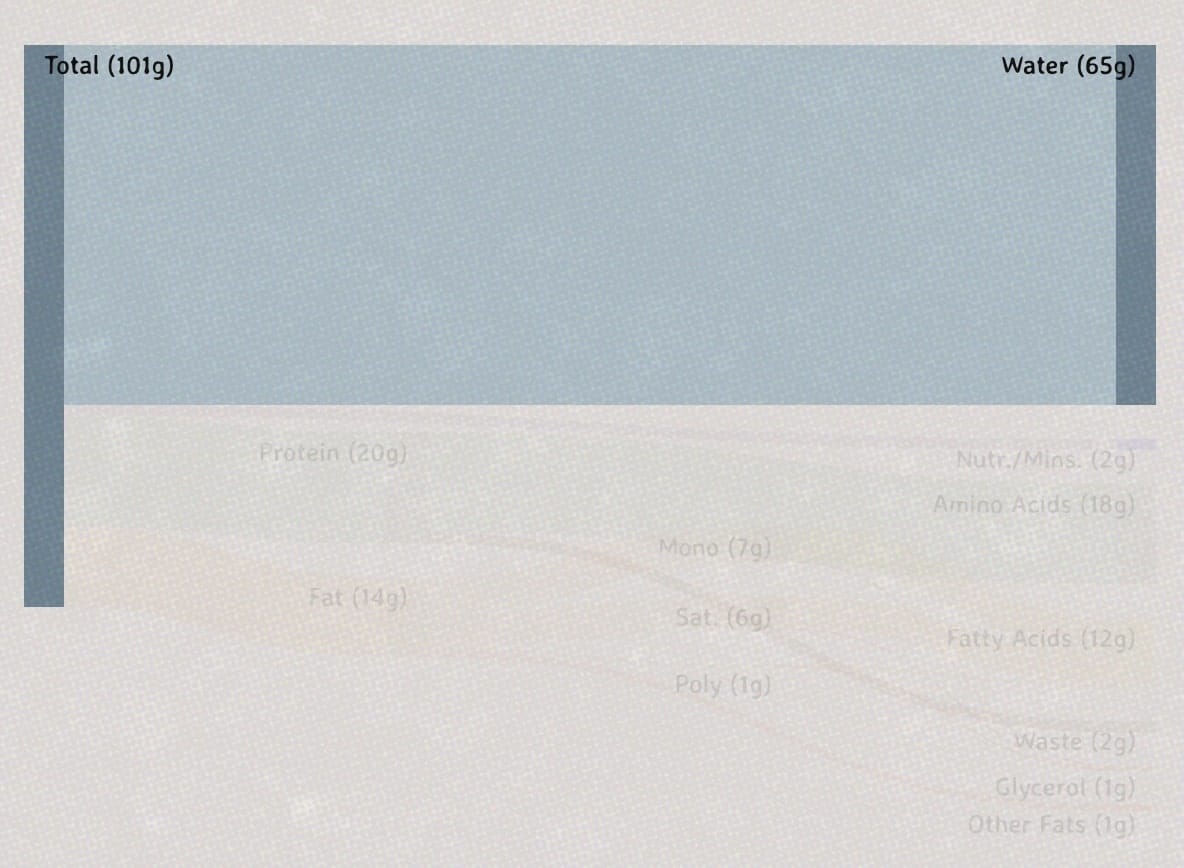

Here’s a look at the primary components of typical foods and what they essentially break down into:

What makes up 100g of food?

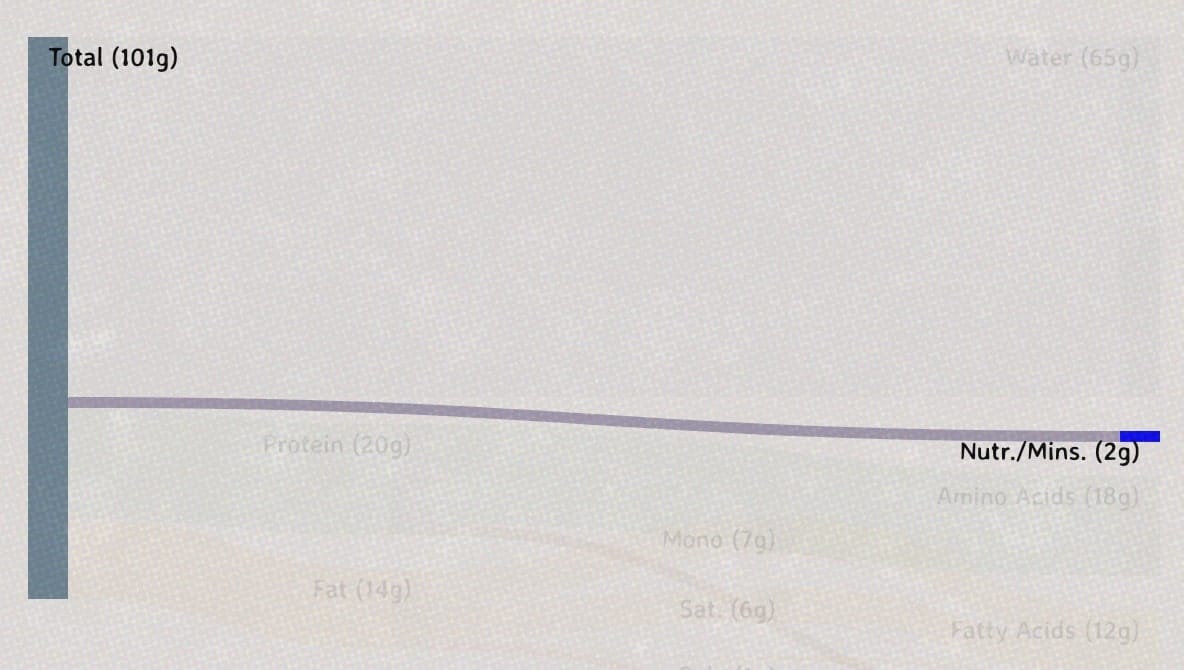

What nutrients make up RAW BEEF STRIPS?

Rough estimates of RAW BEEF STRIPS'S nutrients

Source: USDA FoodData DatabaseWater

Water is the most abundant molecule in most foods, especially in fruits, vegetables, and cooked meats. It can make up about 70% to 90% of some common fruits and vegetables, and around ~60% of meats. Even foods that seem dry, like certain cheeses and breads, can contain water content ranging from 30% to 50%.

When examining a Sankey diagram that compares the nutrient composition of raw and cooked meat, it seems like the proportion of nutrients—such as protein and fat—in cooked meat is significantly higher than in its raw counterpart. This, technically, would imply that cooked meat is ‘more healthy’ than its raw counterpart.

However, this apparent increase in nutrient concentration is not due to any actual addition of nutrients during the cooking process…instead, it’s a result of the change in the water content and overall weight of the meat.

Water is interesting because, consistently, it decreases when cooked. This is because methods like grilling, baking, or frying, which apply heat to the meat, causes the water to evaporate, reducing the overall weight of the meat, or whatever food item you are preparing.

When meat is cooked, it loses a substantial amount of water, typically around 25% of its original weight, depending on the cooking method and duration.

In raw meat, water makes up a large proportion of the total weight— something like 40 - 60%. During cooking, much of this water evaporates, leaving behind a denser product with a higher proportion of protein and fat relative to its reduced weight.

This can give the impression of a nutrient boost when viewed in terms of percentages, but it’s merely a matter of distribution, not an actual increase in the nutrient content of itself.

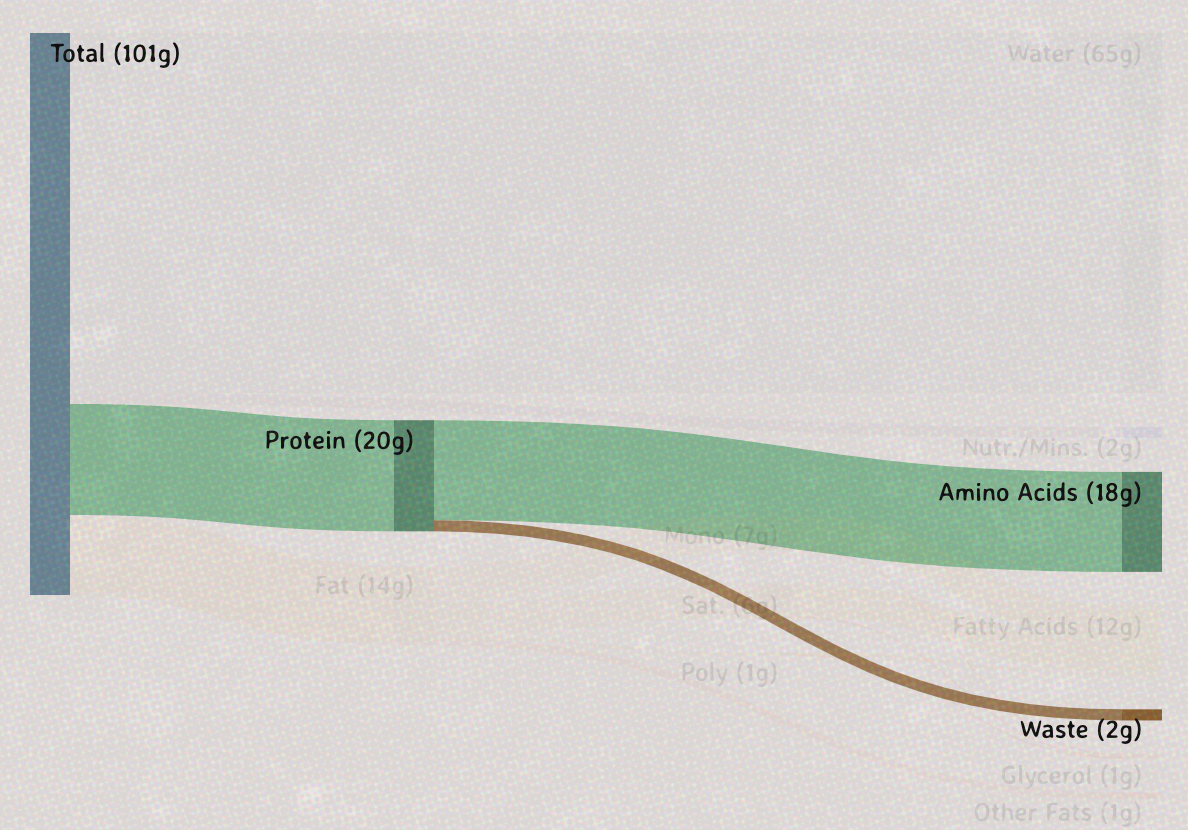

Proteins

Typically, proteins should account for about 10% to 35% of your daily caloric intake. For instance, if you consume about 50 grams of protein per day, these would be broken down into their constituent amino acids for bodily functions. Amino acids are are essential for building and repairing tissues and making hormones and enzymes.

When it comes to cooking, protein levels remain relatively stable. There is no "transfer" of protein during the cooking process; the amount in the meat before and after cooking stays the same. What changes is the concentration due to water loss.

It's worth noting that not all consumed protein is utilized by the body. Estimates vary, but around 10% of protein intake can go to waste due to factors like the digestibility of the protein, the quality of the meat, and the individual's overall health and digestive efficiency. High-quality proteins—those with a complete amino acid profile—tend to be more effectively utilized by the body. Something to consider next time you’re deciding between organic chicken vs Chik-Fil-A.

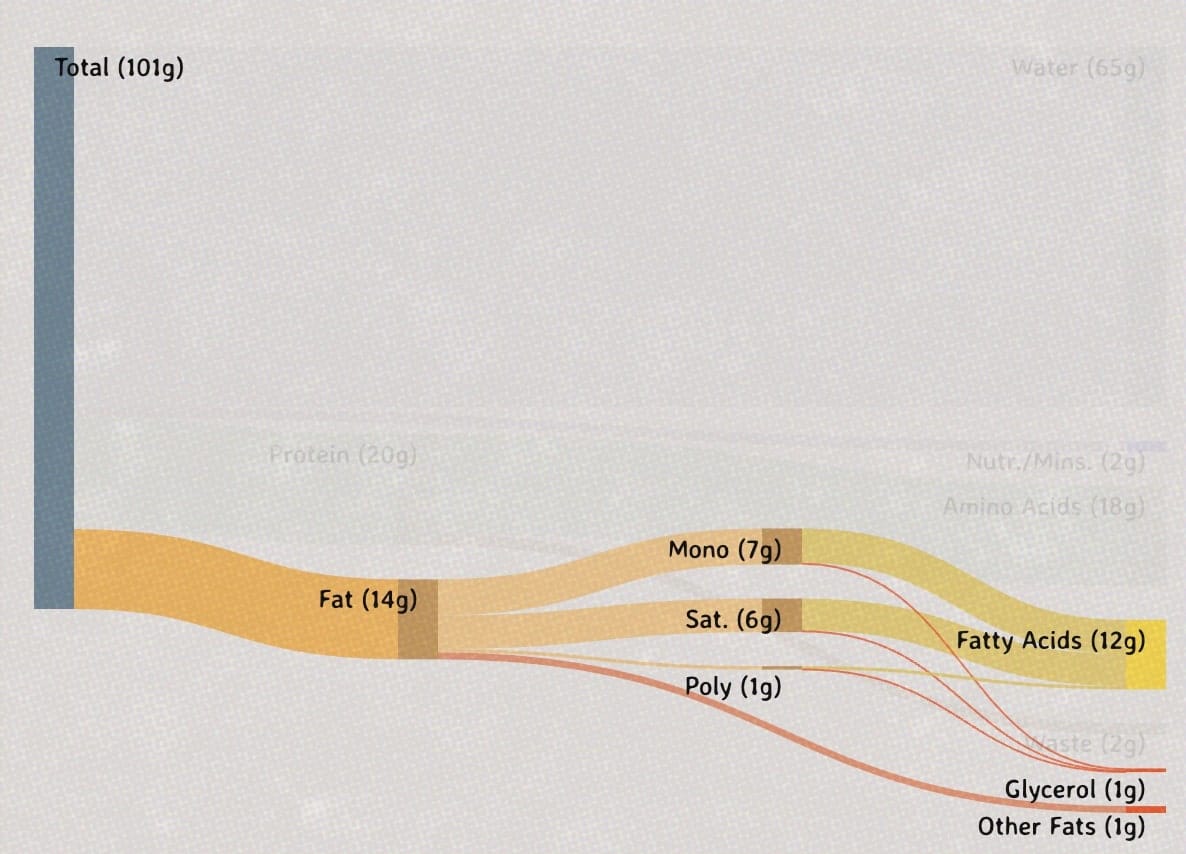

Fats

In a typical diet, fats should provide about 20% to 35% of total daily calories. All fat can be classified saturated, monounsaturated, polyunsaturated or other fats, as I've written more about here. And those four categories are then are typically broken down into fatty acids and glycerol, with about 95% of the fat content going to fatty acids.

When it comes to cooking, fats play an interesting role. If no additional fats are introduced during cooking, the fat content of the food itself remains stable. However, most people cook with added fats, such as oils, butter, lard, etc, so the total fat content of many hot foods often increase when going from raw to cooked. This happens because the food absorbs some of the cooking fats, which become part of its overall makeup and weight.

The extent of absorption can vary depending on the cooking method and the type of food—fried and sautéed items, for instance, are more likely to soak up fats than baked or boiled foods. And this absorption not only increases the fat content of the dish, but also its nutritional profile. For example, frying meat in oil adds both calories and potentially new types of fats to the food (trans fats), which makes cooking methods part of what describes a diet.

Carbohydrates

In a standard diet, carbohydrates can comprise about 45% to 65% of total daily calories. he way carbohydrates are broken down into glucose—a key energy source for the body—depends heavily on the type of carbohydrate consumed.

Carbohydrates, regardless of type, are primarily broken down into sugars such as glucose during digestion. Glucose is then absorbed into the bloodstream, where it can be used for immediate energy or stored as glycogen in the liver and muscles for later use.

Simple vs. Complex Carbohydrates

- Simple Carbohydrates: These are found in foods like fruits, milk products, and sweeteners. They break down quickly during digestion, rapidly converting into glucose. This fast breakdown provides a quick burst of energy but can also lead to blood sugar spikes.

- Complex Carbohydrates: These are found in whole grains, legumes, and starchy vegetables. They are made up of longer chains of sugar molecules and take more time to digest. This slower digestion provides a steady, sustained release of glucose into the bloodstream, offering more stable energy levels.

Like protein and fats, cooking methods affect how carbohydrates are digested. Cooking starchy foods like potatoes or pasta can make their carbohydrates more accessible for digestion, potentially raising their glycemic index (a measure of how quickly a food raises blood sugar levels).

Vitamins and Minerals

While not breaking down further like macronutrients, vitamins and minerals are crucial in small amounts for various bodily functions, from bone health to immune system support. It's always interesting to me how much of our health comes from these micronutrients, yet they only make up 2% of an item's mass.

Something interesting is the concept of Ash; it appears to be more prominent in cooked beef than raw....